During the first year of my Ph.D., I have focused on the accessibility design of touchscreen applications. This interest was motivated by the fact that the older population is increasing globally and older adults are interested in using technology. My grandma (on the photo) is a beautiful example of that. In response to these changes, there is a growing body of literature on how to make touchscreen devices and applications more accessible to them. In our systematic literature review, we look into the last decade of research-based design guidance, analyze it, extract individual guidelines, and categorize them based on two taxonomies: capability model and touchscreen design categories.

The problematic user experience of older adults with touchscreen devices has motivated a wide range of recommendations on how to improve it and inform the design for the ageing population. However, despite the growing effort of the research community, it remains challenging to translate these research findings into actionable design guidelines, which ultimately hurts the development of more accessible interactive systems. We conducted a systematic literature review to examine the research-derived design guidelines that set the foundation for design guideline compilations and standards. Analysing them from the perspective of experts, our goal was to discover, classify, and evaluate the work in the area of touchscreen design guidelines for older adults.

Our study was set to answer the following research questions:

-

RQ1. What are the characteristics of the older adult population and interaction design addressed by current research-derived guidelines for touchscreen?

-

RQ2. What is the quality of the methods and strategies used to generate and validate the design guidelines?

-

RQ3. Which issues emerge and what effort is required in identifying and cataloging research-derived guidelines in order to make them available to the average practitioner?

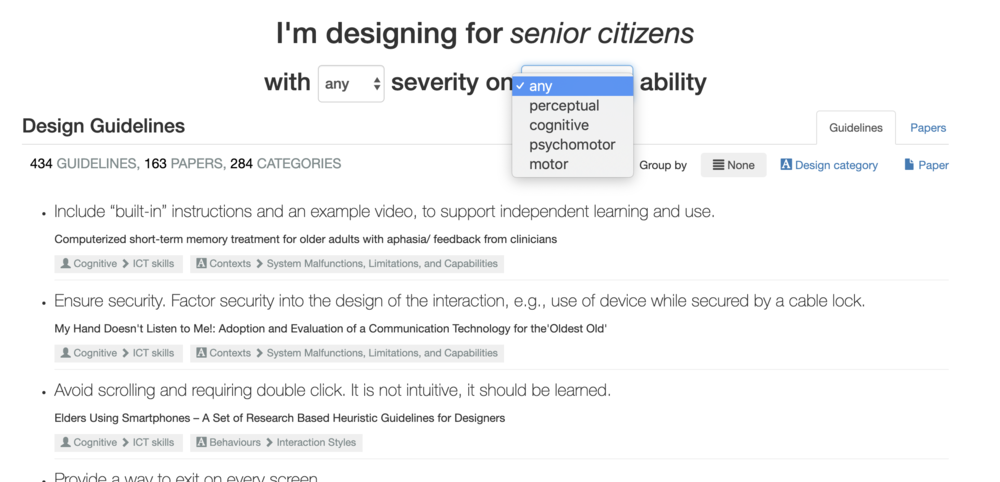

The review included 52 research articles and resulted in 434 research-derived design guidelines. These guidelines were analysed using two taxonomies that considered the ability evolution related to ageing and the touchscreen design aspects.

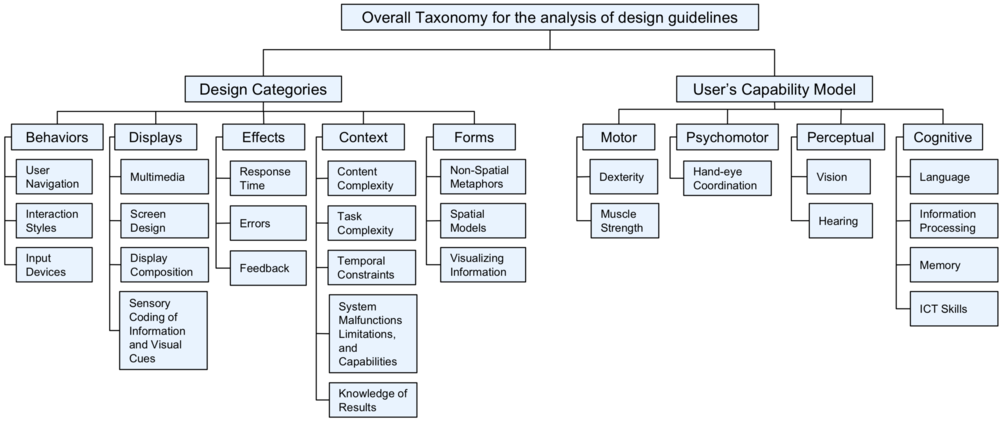

USER CAPABILITY MODEL

To characterise abilities that are affected by ageing, we considered the aspects that define an individual’s ability to interact with a system in a user’s capability model. It was chosen for representing the diversity of the older adult population, and for providing a better understanding of the guidelines that should be enforced according to a specific target, a population with its strengths and limitations. The categories included in the user’s capability are the following:

-

Perceptual abilities, including vision and hearing as primary output modalities in manipulating touchscreen devices;

-

Cognitive abilities, such as working memory, divided attention, and information processing speed, declines of which can significantly affect user’s capacity to interact with technology;

-

Psychomotor abilities, such as slowness and imprecision in motor control and declines in hand-eye coordination, which may make touchscreen input problematic for older adults;

-

Motor abilities, caused by a decrease in muscle strength and dexterity and resulting into mechanical difficulties in navigating touch based applications and devices themselves.

DESIGN CATEGORIES

The design taxonomy indicates that user interface consists of seven fundamental components: Actions, Behaviours, Contexts, Displays, Effects, Forms, and Goals, which cover both design and interaction dimensions users face while using touchscreen technologies.

-

Behaviours, which refers to the user’s interaction styles with the system, its navigation, and information input. For instance, this category includes guidelines on gestures used when using touchscreen devices or possibilities of multimodal data input;

-

Context, which refers to the settings in which the user behaviour can occur and that have effect on the performance of users. Complexity of the system content and tasks related to the navigation are typical subcategories of “Context”;

-

Displays, denoting the visualisation of information for its own sake. Typical guidelines that belong to this category span topics such as multimedia used in the systems or composition of the content, and others related to the displaying information to users;

-

Effects, denoting feedback about the system actions as a response to the user interactions. For example, this category includes guidelines about error messages displayed to older adults;

-

Forms, that refers to models or metaphors in which actions, effects and displays are embedded, for example, in relying on familiar notions to older adults when developing touchscreen applications.

RESULTS

Our review showed that older adults – as a target group that was supposed to benefit from the application of design guidelines – were defined using different chronological definitions, i.e. by age. These definitions were rather general and contained an emerging functional focus, which means they started incorporating ability declines. For instance, “adults older than 60 years with a reduced vision”. As for the design dimension, we identified guideline archetypes – pairs of ability decline and design category – covering the most important ability and interaction design dimensions, such as the design of pictures and/or video to address vision declines or adapt the content complexity to declines in language processing. We also presented the areas related to the touchscreen interaction that are covered more than others, as we wanted to bring attention to their uneven distribution, and indicate the potential gaps that could benefit from future research.

We analysed the papers’ methodology in producing and validating design guidelines with the intention to make the guidelines more useful for designers and developers, to support them in their understanding of the relevance of each guideline and its validity. Our findings are rather cheerless, and indicate the need to validate existing design guidelines and to increase the quality of guideline generation in future.

The question that remains is: “Is there a need for more research in areas that are lacking design guidelines?” or, maybe, by the nature of the type of touchscreen interactions there is no actual need for them. This question becomes even more important, as designers have to prioritise and choose wisely considering the possible compromises and trade-offs, but unfortunately, there is still a little guidance on how to choose and apply available guidelines.

As an attempt to address that need, the final list of included papers and respective guidelines are presented in a repository (http://design-review.mateine.org) as a collection of guidelines derived from our review. We believe, it would allow researchers and developers to apply and consult the guidelines while developing touchscreen application or conducting studies for and with older adults, and has a potential to become a repository to submit new guidelines and make them available for future contributions in this area.

Cite as:

Nurgalieva, L., Jara, J., Baez, M., Casati, F., & Marchese, M. (2019). A systematic literature review of research-derived touchscreen design guidelines for older adults. IEEE Access.

DOI: 10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2898467