The effect the COVID-19 outbreak is currently having on the digital health sector is unprecedented. Still, it is accelerating the trends that were in place before: health apps were already becoming a part of everyday life as daily support for our health. Large numbers of them are created and used more and more for various goals and health conditions: from developing and maintaining healthy habits to supporting people with severe diseases like cancer survivors. Yet, to maximise the positive impact of technology, it is important to guarantee the privacy and security of users’ data. To achieve this goal, it is more important than ever to have clear and valid methods for evaluating the data practices within them.

Recent data protection regulations such as the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) helped to raise awareness and establish a minimal set of expectations. But they are not enough for the development of systems that follow the best privacy and security practices. Research is leading the way, and there is a growing number of studies on the assessment of the privacy and security of health apps, and guidelines to support the design process. Still, it is not easy to navigate this space and choose appropriate techniques for a specific context and requirements.

This challenge motivated us to review literature between 2016 and 2019 on the security and privacy of m-Health applications. We examined security and privacy evaluation techniques and frameworks and design recommendations. Our intention was to support researchers, app designers, end-users, and healthcare professionals (well, anyone who is interested) in designing, evaluating, recommending and adopting health apps. Next, I briefly discuss the findings that I think are interesting and useful.

What health problems are health apps addressing?

Apps in general “health and wellbeing” category were the most popular to evaluate among research studies. Still, when it comes to a specific condition, interestingly, digital mental health was the most addressed when it comes to security and privacy. The motivation to evaluate mental health apps from this angle can be viewed broadly in terms of risks and opportunities. Regarding the risks, researchers agree that by using mHealth apps, people with cognitive decline and mental health difficulties are potentially exposed to privacy breaches. Their data should be protected, and privacy policies should be easily understandable and should not prevent users from making informed decisions.

Still, the potential of mental health apps to benefit users is also high. They can support users in many ways: by increasing users’ understanding of their conditions, by increasing end-user adherence to therapy, and even by complementing or replacing face-to-face therapy when appropriate. However, research is cautioning us that the acceptance of such interventions should be carefully evaluated.

Privacy, security, what is the difference?

Over a third of studies looked at privacy and security together. Indeed, security and privacy might overlap, for instance, in protecting patients’ confidentiality. Yet, these two dimensions have fundamental differences: security is about protection against unauthorised access to data and privacy is an individual’s right to have control over their private information, and relates to trust in digital health services. Keeping the focus only on security can increase surveillance and data collection, which introduces potential privacy risks. Unsurprisingly, the methods to evaluate these two dimensions differ as well: methods for security may place more emphasis on technical evaluation while methods for privacy may be more user-oriented.

Security and privacy Evaluation

Simply put, security and privacy of health apps can be evaluated using technical and “non-technical” (heuristic) methods or tools.

Technical evaluation is, for example, security checks using static analysis to highlight app’s code vulnerabilities or traffic analysis to detect potential data leaks or problems during data transmission. A typical use case is an analysis of the traffic between a fitness tracker and a smartphone app.

As for “non-technical” methods, evaluation of information that comes with an app (self-declared data) was the most common technique for privacy assessment. Privacy policies, terms of the agreement, and informed consent are usually analysed to check whether they are available (on the first place) and actually readable by an average human being (who is not a lawyer). More sophisticated methods compared these disclaimers to the marketing statements of app providers, to determine whether they are consistent with each other, with the regulations, and even with users’ expectations. Unsurprisingly, privacy policies tend to be too complex to read and keep getting longer over time, which doesn’t help either.

Evaluation based on app user reviews was another way of extracting evidence on app security and privacy. There is a separate field of research on the effect positive and negative reviews have on us, like a phenomenon called “negative bias” that makes negative reviews more “influential” than positive reviews. More recent researchers say it’s not so straightforward, as the valence of online reviews is related to their helpfulness: “satisfied customers are motivated to write well-composed and in-depth reviews, while unhappy customers provide less transferable information”. Coming back to the initial point, there is also an increasing market for fake positive online reviews, and evaluation methods based on user reviews might not be reliable as a sole indicator of security or privacy of Health apps.

We identified the critical moments of the mHealth app lifecycle at which specific evaluation techniques could be applied: from the design and creation of an app to the testing and finally, adoption and recommendation to patients. For instance, while at early stages research recommends to check against legal compliance and apps’ security vulnerabilities, at the later stages one could assess apps’ ’ materials and data handling practices.

Paid or free health apps?

Most of the evaluated apps were free, which is understandable. They might be more popular among the users and easier to access by the researchers (it’s a shame, but research funding is not unlimited). Still, this keeps a large area of paid apps untapped by research. Considering the “paying for privacy” misconception – when we think we get better data protection and privacy in paid services – more work is needed in reviewing paid apps as well.

Design guidelines

As we discovered, the guideline extraction process was not always easy. Only one-third of the studies presented their design contributions in the form of guidelines or instructions, which were easy to extract, interpret, and categorise. For the rest of the papers, guideline identification and extraction required more effort and time, as guidelines were presented as experiment outcomes, future recommendations, and observations. This is not a problem per se, but considering the target audience that included developers and designers, it could challenging for them to get the message.

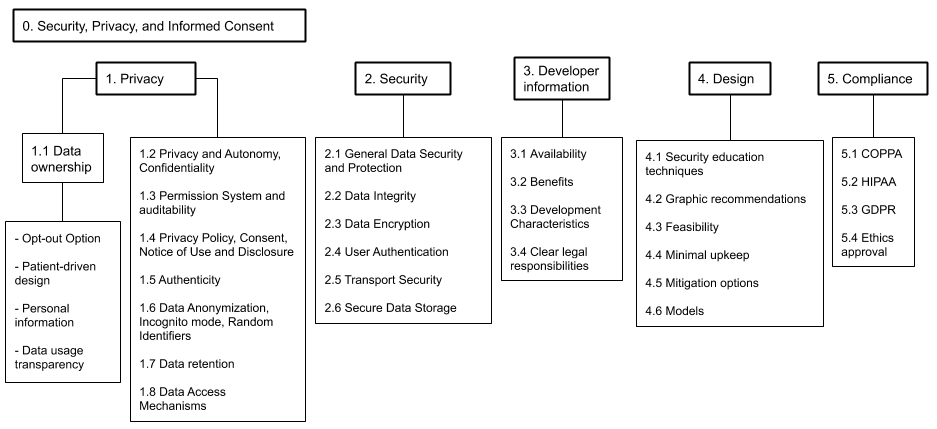

We roughly categorised all guidelines in 6 categories, see the picture below.

Design guideline taxonomy

Privacy-related guidelines formed the largest group, and security-focused guidelines (roughly one-third of all design recommendations) included such topics as secured data transfer, storage, and user authentication.

What could be done better?

We can clearly see that the awareness and research on security and privacy of digital health are growing but still, there are substantial gaps in the field. Inclusive and co-design are well-established concepts, but only a few studies involved health app users and healthcare professionals in the evaluation process. It would also be great to see better work on reporting evaluation techniques and guidelines that come from research, which would make them more accessible and applicable. We also need more effort in validating and reproducing findings to have more reliable and actionable research guidelines.

The evaluation frameworks, techniques, tools, and design guidelines extracted from the literature form a knowledge base. We hope that it will be useful when developing health apps. We are planning to make the findings available in a more accessible fashion (like we did with accessibility guidelines in previous work), but if you have questions, feel free to reach out!

Refer to this publication:

L. Nurgalieva, D. O’Callaghan and G. Doherty, “Security and Privacy of mHealth Applications: A Scoping Review,” in IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 104247-104268, 2020, doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2999934.