I work as a postdoc, but how did I come to this? How does one become a postdoc? Here is the second part of the answer to this question; please, see the first part here: How does one become a postdoc? My story (part 1)

Towards the end of the PhD, everyone starts thinking of “what’s next”. There are different paths one can take after adding a Dr to their title. In computer science, you are often asked whether you want to stay in academia or switch to industry. There can be options to combine both, for example, R&D positions within companies where you get to do more or less applied research. Usually, it is “more”, but I have heard of places like Google’s DeepMind, famous for their research freedom.

I was no exception. In addition to the constant and always unsuccessful quest to reduce uncertainty in my life, being a non-EU in the EU means that you always need a formal reason to stay abroad, which was another motivation to start actively searching for the next positions. Postdoc looked like a logical choice for me at that time. In Italy, it was usual to work as a postdoc after your PhD, and postdoc positions were often advertised on the newsletters of research communities I am part of. Besides, I liked doing academic research, there were topics that I wanted to study deeper, and I had several projects to be completed – PhD research studies do not stop after you get your degree.

What is a postdoc?

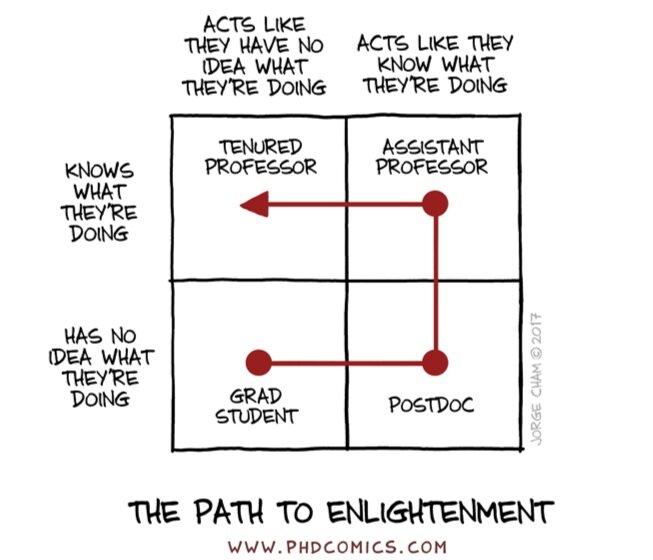

A postdoc is a strange time in the academic career, which is confirmed by lots of funny comic posts on phdcomics.com. I guess, depending on such factors as one’s research experience and independence, the supervisor/ PI, and the research group’s work culture, it can be a very different experience for different people. Postdoctoral positions can be offered by: (a) an academic department and typically come with formal teaching duties; (b) a faculty member and are funded by a grant; or (c) a national fellowship or a fellowship from a foundation, in this case, you are often free to choose the host academic institution. Usually, it is a relatively short time (up to a few years) to gain more independence and expertise, expand your network, publish papers, get some teaching and even supervision experience to have a stronger profile and CV to apply for more advanced academic positions. The drawbacks are also important to consider, as postdocs in academia are paid substantially lower than colleagues with roughly comparable education and experience (e.g., junior tenure-track faculty and colleagues in the industry). In some universities, postdocs are not considered employees. They, therefore, are provided fewer or lesser benefits in areas such as health care, retirement, or access to childcare (depends on the country). Postdoctoral position usually is taken shortly after completion of the PhD, and it is often a time to start thinking of “settling down” (whatever it means), and a 1-2 year contract, often in another country, might not be the most convenient option. However, a postdoc is also not an obligatory step for that and more permanent academic positions like a lecturer or assistant professor. There are situations or countries where it is normal to get them right after your PhD.

Searching for computer science postdoc positions

As I said earlier, the easiest way (I think) to find relevant postdoc positions is to subscribe to the newsletters of your research community, for example, CHI-JOBS (SIGCHI mailing and discussion lists) for HCI-related positions or cvml (Computer Vision and Machine Learning) email list. Research groups and PIs often advertise them there and provide contact details for related questions. Other ways to search are websites like EURAXESS for academic positions in Europe or Times Higher Education for a more global view. There are also websites of the funding bodies or institutions specifically, which can be both regional and global, for example, positions by ADAPT or LERO that are research centres funded by Science Foundation Ireland. Finally, by the end of the PhD, one usually already has some network and knows people from other research groups, and “Word-of-Mouth” peer advertisement should never be underestimated. For my first postdoc, it was the latter. I knew my PI from the EIT Health summer school that I learnt about from my EIT Digital training network (it was an “extension” of my PhD studies) and followed him on Twitter, where he advertised the position.

Next, I’d like to share my knowledge and experience of the application process for a Marie Skłodowska-Curie (MSCA) COFUND postdoctoral fellowship. As a disclaimer, this information is mainly based on my personal experience. It does not reflect any official guidelines (please, check official websites and documentation for that), and it is also possible that they might have changed since I applied.

Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions (MSCA) COFUND postdoctoral fellowship

First or all, what is Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions (MSCA)? MSCA funds different types of postdoctoral fellowships: individual fellowships (IF) and fellowships through cofunds. Both of them are for international mobility, which means that researchers can only apply for a position in a country where they have not resided or carried out their main activity, work or study, for more than 12 months in the 3 years immediately prior to the call deadline. From what I have heard, IFs are fully funded by MSCA and provide the freedom to choose a country and hosting institution but also harder to get, and the application requires a longer preparation time. Some institutions even have the scholarship to fund researchers during this period, such as last year “UniTrento call for Expressions of Interest – Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellowships 2020“ (University of Trento). I did not try applying for it, so I recommend reading more about it on the MSCA IF official website.

Now, what’s about the COFUND? MSCA can also co-fund regional, national or international programmes to “enhance excellence in research training, mobility and career development. Programmes”, which open up to and provide for “international, intersectoral and interdisciplinary research training as well as transnational and cross-sectoral mobility of researchers”. Research institutions apply for the funding and then open a call for postdoc positions, which means that the application process is similar, but – unlike individual fellowships – the location and institutions are pre-selected, and the applicant sends the application to the regional research centre and not to the EU Commission directly.

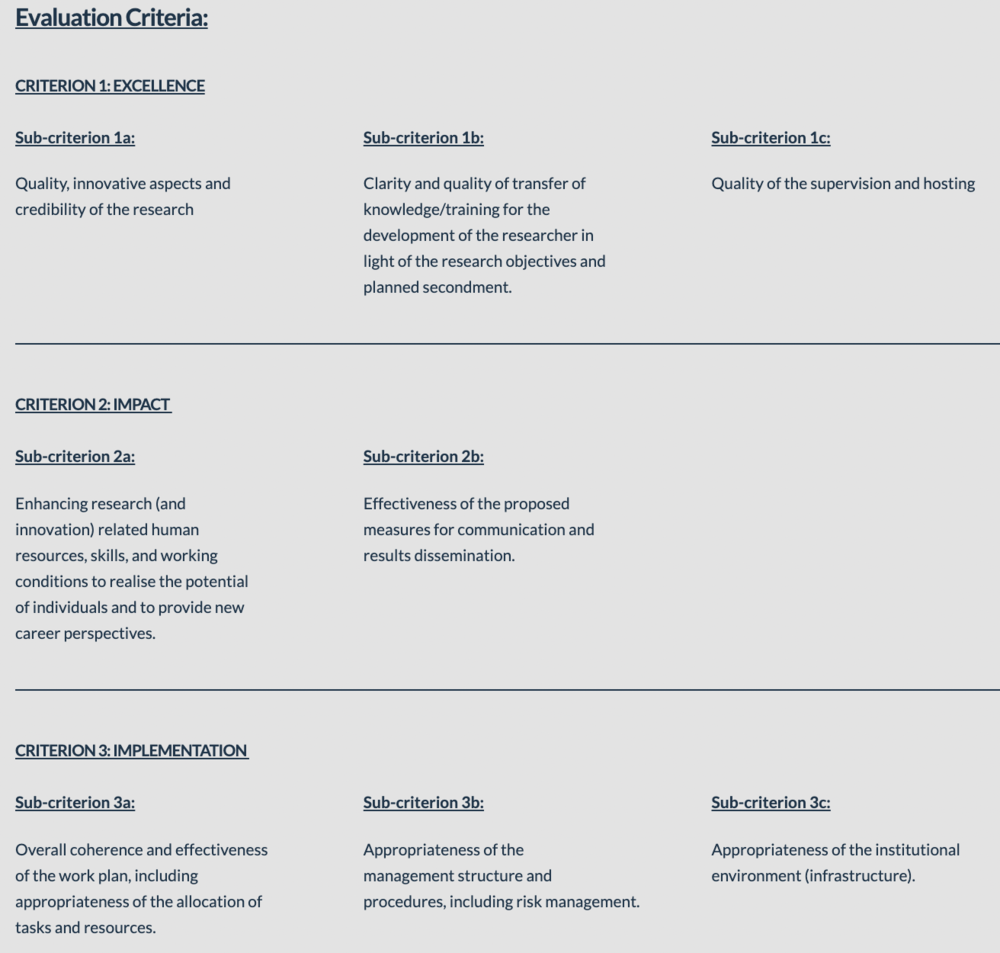

Evaluation criteria and scoring system – ALECS, MARIE SKŁODOWSKA-CURIE FELLOWSHIP AT LERO, THE IRISH SOFTWARE RESEARCH CENTRE

Application process follows six stages:

Stage 1: General eligibility check

Stage 2: Ethics check. All candidates must indicate whether or not there are ethical issues associated with their proposed research and – if ethical issues are flagged – submit an *Ethics Self-Assessment”.

Stage 3: International peer review. The evaluators are experts (=researchers) in the field who will be matched to your proposal according to their profile and to your abstract and keywords. They will for sure be in your general research area, but might not be in the exact same field that you are. Every proposal is read and evaluated by at least three independent evaluators. The evaluation criteria is similar to IFs and includes the following criteria – see the picture on the left (taken from the ALECS COFUND fellowship website I have applied for).

Stage 4: Ranking of applications

Stage 5: Interviews where candidates will be asked to give a 10 minute presentation on his/her research proposal, which will be followed by 40-50 mins of Q&A (also based on the submitted research proposal).

Stage 6: Ranking of applications and final funding decision.

What I found very helpful is that I was able to ask the Research centre my questions related to the application process and got lots of support. Overall, the application process went well, and I moved to Ireland to join Trinity College Dublin as a postdoc. Shortly after, a pandemic hit the world, which negatively affected my postdoc experience, but that’s another story. It took some time to figure out how to postdoc, as it is a new role different from a PhD, and I find these recommendations of the National Academies’ report very helpful. Before starting a postdoc, it is good to discuss the following questions with the prospective advisor and even current and former postdocs who have worked with them – I didn’t do it, but I know postdocs who did and found it very helpful:

-

What are the advisor’s expectations of the postdoc?

-

Will the advisor or the postdoc determine the research program?

-

How many others grad students, staff, and postdocs now work for this advisor?

-

How many postdocs have the advisor had, and where did they go afterwards?

-

What is the advisor’s policy on travel to meetings? Authorship? Ownership of ideas?

-

Where are the papers or conference proceedings being published?

-

Will I have practice in grant writing? Teaching/mentoring? Oral presentations? Review of manuscripts?

-

How long is financial support guaranteed? On what does renewal depend? Will the advisor have adequate funds to support the proposed research?

-

Can I count on help in finding the next position?

-

What do current and past research group members think about their experiences?

As my PhD lasted only 3.5 years, I found the postdoc time beneficial to grow my independence and confidence, learn how to lead research projects, and take up more responsibility. I liked my research group and working with my PI, and there were options to extend the contract or find another position, but I decided to leave Ireland for personal reasons. So overall, despite the pandemic, my experience was quite positive, and I can recommend doing a postdoc. In fact, I just started my second postdoc, and let’s see how it is different from the first!